I have worked in what I consider the nonprofit sector for almost fifteen years. My current employer is a research and communication center within a university, so some might argue I’m in the academic sector now. However, my program (and my work) is funded by USAID and operates in the global public health sphere, which makes me feel like I work for a non-governmental organization. That’s not the nomenclature problem. The problem is with the terminology surrounding the global distribution of wealth, power, and certain kinds of economic development.

I’m not denying that there are inequalities in play—countries that give or receive aid, export more than they import, have or don’t have certain kinds of industry and infrastructure, or are above or below the global gross domestic product per capita average. But I think it’s a false dichotomy, and the nomenclature around it is deeply unsatisfactory.

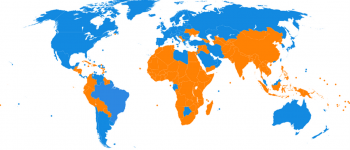

Right now the in-vogue term for countries that (for lack of a better term) I shall call the “economic-industrial-have-nots” is “the Global South”, or just the South. These countries, and the people who live there, are called Southern. Communication and cooperation between them is called “South-South”. This makes my teeth hurt, because of geography. Here’s a map from Wikipedia of the countries above and below the average GDP per capita line.

Yep, a lot of the blue (more-money-than-average) countries are in the northern hemisphere–which by the way includes nearly all of Asia and about half of Africa (I’m not sure, because my brain has been warped by the Mercator projection). There are a lot of blue countries in the southern hemisphere, too. Imprecision bothers me.

I don’t object to having gotten rid of the term “third world countries”–I don’t hear it any more from people in my professional space. “Developing countries” was in vogue for a while, which seemed better, but then as the director of my project noted the other day, “It’s not like a country crosses some magical line and doesn’t have any more progress to make.” Some people were using “emerging markets” for a while (and might stil be), but I find that pretty insulting–as though people in the international development sector are there solely for the purpose of selling people things. (I’m not saying that isn’t *a* reason. But it’s not the only reason. And it’s certainly not my primary reason for doing the work I do.)

I think I’m also irritated because the “rich/poor”, “industrial/agrarian”, “democracy/dictatorship” dichotomies deal in such a narrow sphere of human value. They all split the countries up and attempt to name them as two groups by reducing people to dollars, or voters, or oppressed masses. I think it’s too simple.

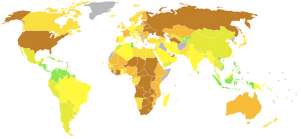

And yes, I recognize that my discomfort with the nomenclature is a First World Problem, and I’m having all kinds of guilt about my carbon footprint and disproportionate consumption of all sorts of resources. But here’s a totally different map–a scale, not a dichotomy:

This is the Happy Planet Index map. It’s about ecological footprint.

Surprisingly, I’m having trouble finding a map of happiness, or fulfillment, or peace, or connection, or time with family, or any of the other things that count to me as a person to my quality of life.

So, I’m on the lookout for an evolution in the nomenclature. I’ll keep you posted.

Update! Sept. 25, 2013: No evolution in nomenclature, but a new report on global happiness from the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN), a nice post about it on Columbia University’s Earth Institute website, and a digital publication version. Sadly, still no map.

Update 2! Oct. 15, 2021: Nomenclature!! I just heard the term “Majority World” for the first time. It’s a great phrase, although I’m struggling with some imprecise nuances. I’m also annoyed that I haven’t heard it before, despite it having been coined no later than 2009 (the publication date on the article I link to above). Diffusion of innovations is an interesting thing.