(This is mostly about body painting, but if you like you can skip down to the bit about the colors you can get using woad as dye.)

Caution: Woad can cause allergic reactions and irritate eyes and other sensitive areas. Your use of any techniques or instructions herein is at your own risk. Be sensible.

TL;DR: For quick reference, here’s just my recipe: 1 packet (5g) powdered woad pigment, 2 tsp whisky, pinch of rosemary, wet-ground in a mushroom-shaped mortar and pestle. That makes a concentrate. Mix 1/2 tsp of the concentrate with another 1-2tsp of whisky to achieve your desired coverage quality. Many, many more details below. Gum arabic is optional. I’ve started but not completed some chalk experiments.

I’ve been using woad (a dark blue pigment derived from a plant also called woad, Isatis tinctoria) as a body-painting pigment since the late 1990s, in the context of an Iron Age Celtic reenactment/living history group. This post originated as a write-up of my experience for use at an Arts & Sciences class at Pennsic XLV. [Note from Jan. 2018: I update this post once in a while with more photos, measurements, and technique refinements.]

Pennsic is an event of the Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA). My group, Clanne Preachain, is an independent “non-Kingdom ally”—many of our members are also SCA members, but I’ve never been a card-carrying SCAdian.

These are my notes about how I adapted woad lore and research for use in the modern reenactment context. My goal here is to share what I do—not to convince you that insular Celts and/or Picts definitely, for sure, really did use woad as body paint and/or tattooing pigment. (Maybe they did. Maybe not. There are strongly differing opinions and contradictory research.) But “The ancient Britons painted themselves with woad” is traditional lore in England. I learned it as a child, as “part of the rich tapestry of our island story” (as P.G. Wodehouse might put it). If anyone wants to argue about this during class, we can—but putting that question to rest is not my primary goal.

The most useful summary of sources (including many of the controversies over translation and source reputability) and techniques that I have come across is Gillian Carr’s “Woad, Tattooing and Identity in Later Iron Age and Early Roman Britain” [see note 1]. I read the paper some time ago, but it was recently brought to my attention again by Lah Jurca, who is the motivating force behind me teaching this class (and who has made this “Woad Map” handout with a lot more information).

Clanne Preachain is not a reconstructive archaeology group; we strive for a tribal, mythopoetic, and artisanal authenticity from a practical, modern standpoint. For example, we do much of our cooking on braziers, but our Pennsic kitchen also has a propane camp stove. Sometimes we cook things we gathered, grew, raised, or hunted; sometimes we go to Costco. I bring my woad kit and a drop-spindle to events, along with pharmaceuticals, dental floss, and whisky.

Preachain accumulated a great deal of experience with woad as body paint before I joined in 1997. The group had tested several techniques. Mixing mediums included egg whites, water, saliva, beer, and beef fat—none of which were ideal in our context (for hygienic and aesthetic reasons). Some practitioners used brushes for application; others used cosmetic grinders, fingers, or charcoal smudge sticks.

These approaches had many drawbacks in our modern reenactment context. Typically, in our group, many people want to be painted within quite a short time, so a bulk grinding technique is necessary. The designs need to dry quickly. Most of our events take place in much warmer climates than insular Celts would have had to deal with, and some materials spoil too rapidly in the heat. I didn’t like the smudge sticks as an implement (both for their modern appearance and the quality of line). I tried several different approaches before settling on my current techniques and materials—and I encourage you to do the same. Here’s what I do.

Materials

- Kit containment: You’ll want a basket, a box, or at least a pouch to keep your kit in.

The front of my woad chest

Wingaling owls on the top

Little compartment in the lid for brushes + a tray for small bits on top

Spacious bottom compartment Pouches tend to mash brushes, though. Mashed brushes are hard to paint with. [EDIT: Thanks to the amazing Cassandra Sherman, I have what I honestly believe to be the Most Magnificent Woad Chest on the Planet. I debated about whether to post it here because I don’t want to make anyone feel bad about their woad containment. But that’s balanced out by my gratitude and wanting to show off Cassie’s work. Maybe I’ll pull these photos into a separate post…]

- Powdered woad pigment: The Limner’s Guild booth at Pennsic has carried pure Scottish woad for years (and the new management assures me they will continue to do so). Woad should be available from the Guild’s website shortly as well. [EDIT: As of June 2020, woad is not listed on their website, but I have found them quickly responsive to “Contact us” requests.] Other sources include the Woad Center and All About Woad (both in the U.K.). {Tangent: If you want to grow your own woad, excellent instructions for extracting woad pigment (“indigotin”) from the leaves can be found on the “All About Woad” site’s Woad Extraction page. I have never extracted woad myself. Woad can be grown successfully throughout much of the U.S., but check with your local agriculture extension service, as in some places it is classified as an invasive. My sister Michelle Parrish is a natural dyer and master weaver, and has many posts on her blog about her adventures growing and processing woad. [Side note from the tangent: I am intrigued by this “Ancient Blue crystal woad,” which is a stain as opposed to a surface pigment—it’s made by interrupting the extraction process before the pigment precipitates. It’s derived from indigo, not woad (same pigment, different plant), and I haven’t tried it.]}

- Mortar and pestle: I tried a museum reproduction cosmetics grinder (very similar to the one at top right in the museum photo above); it worked very well, but only on tiny amounts of pigment at a time. For the number of people and the scale I usually paint at, it wasn’t enough. I eventually settled on this “mushroom” style. [EDIT: I have been considering a glass muller and plate—I imagine it would avoid the blurping issue, but be much less portable.] Most stone or ceramic mortar and pestles (mortars and pestles??) would work, I think, but I imagine the tactile clues to a perfect grind would be different.

- Whisky: It’s not documentable to Preachain’s period (which is just pre- and post-Roman contact among the insular Celts), but high-proof liquor is my favorite mixing medium/solvent. I use whisky. There is evidence of distillation in Mesopotamia as early as the 2nd millennium B.C.E, but nothing documented for the British Isles until the 15th century A.C.E. Alcohol evaporates quickly off the skin, so the pattern sets quickly—important to our context of “Everyone get woaded and go somewhere together!” I think whisky’s slightly resinous quality does nice things for the paint consistency; vodka hasn’t worked as well for me. Alcohol also evaporates out of the woadbowl before any noticeable nastiness develops. It leaves something quite similar to ink-cake, that can be re-used just by adding more whisky. What not to use:

- Ammonia. Don’t do it. Despite persistent and passionate rumors to the contrary, it does not make the woad stay longer on your skin. It could irritate your skin very badly. And it’s nauseating to paint with.

- Wine, beer, and other alcoholic liquids with residual sugar get sticky and itchy on the skin, attract insects, and can mold or turn to vinegar in the bowl. Not desirable.

- Egg white and egg yolk flake off the skin once dry, and foul the bowl quickly unless you rinse it out frequently, which wastes an awful lot of woad.

- Saliva on its own is loaded with potential ick.

- Water is OK, but drippy to paint with and takes a long time to dry (which is fine if you’re lazing around painting all afternoon; not so much when everyone is trying to get out the gate).

Me, with paintbrush, painting one kinswoman while having my hair done by another. Photo by Derek Nestell, used with permission. (I also enjoy and am slightly embarrassed by the jumble of modern and period-appropriate stuff in this picture.)

- Powdered rosemary: Optional. A pinch of rosemary in the grind takes the edge off woad’s pungent, wet-dog odor, toning down the more objectionable notes. Adding it into the grind, not the mixing bowl, ensures that it doesn’t affect the coverage quality. If you’re at Pennsic, Auntie Arwen and Brush Creek Wool Works might carry powdered rosemary. I get mine from Penzeys. Another woad-painter I know used to put a couple of drops of lavender oil in her woadbowl for the fragrance, but I didn’t like what that did to the coverage quality (for me—her woad was always beautiful). Now one of my campmates is anaphylactically allergic to lavender, so it’s not an option.

- Gum arabic: Optional. Some years ago (2012 or ’13, I think?), Johann Blau (a longtime SCAdian and armorer of some note) was watching me paint, and asked if I ever use fixatives. I said “Like what?” He said, “Well, my mom is a limner, and she uses gum arabic.” I got some at the Limner’s Guild and tried it. It works well: A bit in the painting-mix makes the coverage smoother and less apt to rub off accidentally. Gum arabic is documentable to antiquity as a trade good in North Africa and the Mediterranean—not very likely to have made it to Britain, but not impossible. I just read that gum arabic is insoluble in pure ethanol, so though it seems to dissolve well in the woadbowl, I’m going to test different batches—one with the gum added as I have been doing, and one with the gum dissolved in water first (hoping to get that test done during the first week of Pennsic). EDIT: I did, in fact, test this out, though I failed to document it thoroughly. I took two small corked glass vials. Into each, I put 1/4 tsp of gum arabic. To one I added 2 tsp water; to the other, 2 tsp of whisky. I corked both vials and shook them up thoroughly. The gum dissolved readily in the water, forming a very slightly cloudy liquid. The gum did not dissolve right away in the whiskey; it formed a little stubborn glob. I shook the vial every 8 hours or so, and after about 36 hours the gum had dissolved fully. So now I carry a little gum-mixing-vial in my woad kit, and mix it down with whiskey, and add about 1/2 tsp of the solution to my woadbowl. I’ll try to get better measurements/proportions/photos next time… ANOTHER EDIT: Ugh, gross: Apparently if you mix down a bunch of mix with gum arabic in it, and then let it dry into ink-cake, it is much more prone to mold than if it had no gum arabic in it. I lost a huge batch of mixed woad this way after Pennsic 46. So, mix as you go, or use it as a topcoat (see below).

- Woadbowl: I don’t like to paint straight from the mortar, because it’s heavy, and I have tendon problems in both hands. The painting-mix is a little bit sticky, and can make the next grind clumpier and more difficult if you make the mix in the mortar. For your woadbowl, find something non-porous that fits your hand comfortably. Ceramic or glass cups, small bowls, or scallop shells work nicely. (The one I use is from Maggie the Potter at Feed the Ravens.)

- Storage jars/vials: Up to you. I use small corked clay jars from Dancing Pig, corked glass vials from Bitty Bottle, and a birch box from Feed the Ravens.

- Brushes: Cosmetics grinders have been put forth in the scholarly literature as all-in-one grinders and applicators, but I didn’t enjoy them as an artistic tool. They don’t offer enough control for the kinds of designs I was after. I have tried a lot of brush types. My favorite: the Winsor & Newton Squirrel Mop series. My not-very-deep inquiry suggests that the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans used squirrel brushes for painting and cosmetics, but I don’t have research to support that (yet). Squirrel mops are widely available at art supply stores and online. I like the look of them. With their wire-wrapped goose-quill ferrules, they aren’t obviously modern from a few feet away. I use size 000 or 00 for faces, and size 1 for larger body pieces. They hold a lot of color, and the line quality works well for my style of painting—I don’t feel like I’m fighting the brush to get the line I want, most of the time. Oddly, squirrel mops are not featured on Winsor & Newton’s USA/Canada site, but they are on the UK site and on Amazon.com.

- Chopstick or scraping stick: There’s a fair amount of scraping and chipping of dried woad involved in this process. Using your brush handle is tempting, but the chipping wears the handles down and makes them prone to splitting. I have a special carved stick that I got from Feed the Ravens. A wooden or bamboo chopstick with a tapered shape would work fine.

Grinding

I have found woad pigment for sale in two forms: Chunks, and powdered. The chunks take longer to break down, but even the pre-powdered form is not fine enough for my liking. The grains clump and leave visible streaks. I developed a wet-grinding technique to overcome this. It is best learned in person; the clues to a correct consistency are tactile. I start with a packet/5g of woad powder in the mortar, and add a pinch of powdered rosemary. Then I take a sip of whisky and spit it into the mortar. I could measure as I do this, I guess…but I think the saliva is important. (If you aren’t comfortable getting a little bit of my spit on you, I’m not the painter for you. This is a tribal-identity activity we’re talking about. Friends and family.) Grind carefully—the mixture oozes and blurps over the edge of the mortar easily. At the beginning, you can feel/hear the grittiness of the grain size. After about 10-15 minutes (?) of grinding, the mix changes and takes on what I call a “silky pudding” consistency—the grittiness feels suddenly gone. At this point I scrape the paste into a holding jar. It’s very concentrated, and it doesn’t matter if it dries out.

Mixing into Body Paint

Put about 1/2 tsp of paste into your bowl and add a bit of gum arabic. I measure the gum arabic with my brush—about an inch of gum along the brush handle. This would be easier with photos. [EDIT, 2017: Following last year’s experiments, I now use a gum arabic/whiskey solution which I prepare in advance instead of the powder…and I only mix enough to use in a day, not a big batch in advance because of the mold issue mentioned above.] Then, take a sip of whisky and spit it into the bowl. Mash the paste into the whisky with your stick, then mix with your brush until smooth. You’re going for a consistency between ink and poster paint. Test it on your hand to check the coverage quality. I’m sure that’s a personal preference.

Painting

Advise first-time woad recipients that woad can cause allergic reactions, and that if they get more than a tiny bit itchy or have any other allergic symptoms they should wash the woad off, take some Benadryl, and seek medical assistance as necessary. (I have painted hundreds of people, and have seen two instances of allergic reaction—one immediate, and one that didn’t emerge until the next day.)

Don’t paint above someone’s eyes during the day or on a warm night unless they know what they are getting into. Woad in your eyes stings.

[New information from Pennsic 46: After your woad has dried, you can use the gum arabic solution as a topcoat—it’s great for a photo shoot or other short-term need. It really keeps the woad in place. BUT after a couple of hours, it flakes off—and it flakes *completely* off, taking the woad with it, rather than smudging off gradually. So, no topcoat is better for longer wear.]

This process will not stain skin, but it can be difficult to remove completely all at once. It can typically be removed with a baby wipe or with soap and water. Woad comes off oily skin more easily than dry skin. The woad can get rather deeply into some people’s pores, and take a couple of scrubbings to remove. It will rub off onto your bedding (or your partner(s)) if you go to bed with it still on—but in my experience, it washes out quite easily. (It generally won’t stain fabric permanently unless you use a mordant and/or dip the fabric/fiber in the woad vat before the color has precipitated out. If you have gum arabic in the mix, it’s harder to wash out, but not impossible.) I have seen woad designs stay on skin for as long as four days before the detail is all rubbed out, leaving a dove-grey shadow. If you re-paint the same design in the same place for several days, or just one day with a lot of sun exposure, you can get woad tan lines/shadows.

It’s best to paint on clean skin, or over a dimethicone-based primer. Sunscreens and most other makeup can make the woad bead up and not stick well. Very oily skin can do the same thing, so I’ve considered having some witch-hazel cotton pads in my kit for skin prep. I am also mulling over some tallow-and-beeswax experiments for daytime use (thinking that a lip balm/wax pencil kind of texture might work better than the alcohol suspension over sunscreen and makeup, as well as on oily skin). But grease never dries all the way, making it more likely to smear and get on other things. Maybe a chalk dust/woad powder over the paint to set it? More tests needed…

The design style is completely up to you. I started with freeform doodles, then got more serious with typical La Tène motifs from coins, stonework, and metalwork. I have gradually developed a personal style that works with musculature, bone structure, and light. I think it’s recognizably “Celtic,” but I can’t make any claims to documentation (except for “Get out the gate!!” woad–for that I tend to use simpler patterns, very much like those on the coins in the research paper cited above).

Bonus! Woad as a dye plant: Much more than just blue.

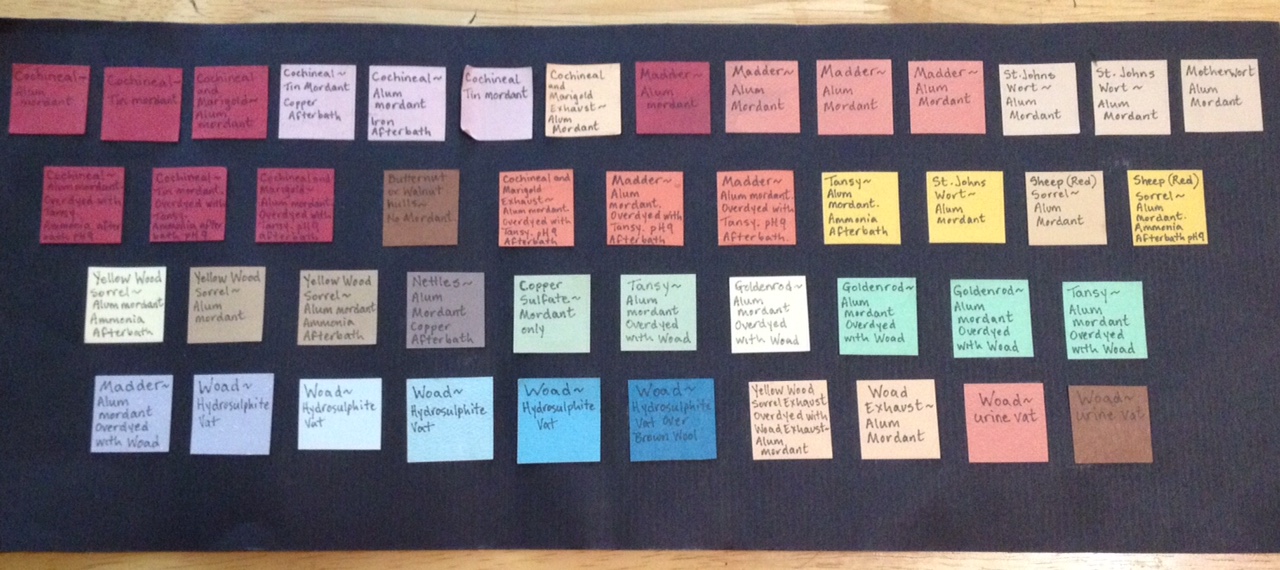

As noted above, my older sister Michelle Parrish is a natural dye expert. Years ago, when Preachain was still doing public living history demonstrations at Celtic festivals, Michelle made me an amazing gift: A sampler of hand-dyed, hand-spun wool, with a key to the plants, insects, mordants, and processes she used to dye each sample. Fifteen of the samples—ranging from a pale green through many shades of blue and a couple of rosy-pink-taupes—are colors derived at least in part from woad.

Key: I started typing these out, but they’re very difficult to parse. Here’s a tiny, hard-to-read photo of the key.

I think Michelle would want me to note that many of the red samples are dyed with cochineal, which the Celts would not have had (as it originates in South America). However, another insect, kermes, produced the same color and was a common Mediterranean trade good in antiquity. It’s comparable to the switch from woad to indigo as primary source of blue. (Woad and indigo both produce “indigotin” pigment—it’s chemically identical, but it’s more concentrated in the indigo plant and less labor-intensive to extract.)

[1] OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY 24(3) 273–292, 2005; © Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2005, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street Malden, MA 02148, USA. The copyright terms of this paper are such that I may not link to it from a public website or distribute it via listserv. I am allowed to email single copies for personal use, though. Go back up to reference point.